File Structure of the Tesla Wall Connector Firmware

Motivation

I found myself scrolling through the r/AskReverseEngineering subreddit and stumbled onto this post that caught my attention. I thought it might be neat to dig into the firmware and see if I could find anything. I have been looking into unicorn mode for AFLplusplus recently. Getting the wireless portion of the wall connector’s firmware loaded up in Ghidra may lead to some interesting findings.

As pointed out in the blog post, you can download the latest firmware directly from Tesla or Firmware 23.8.2, which I did to play around with.

The Firmware File’s Header

When looking at firmware files, my go-to application is 010 Editor. For today’s purpose, we’ll use its powerful template capability that makes breaking down binary file structures a lot more intuitive.

Up front, the first 4 characters of the file are ASCII, which can often indicate a file signature or magic. In the case of the wall connector’s firmware, we see SBFH. It could mean Something Bomething Firmware Header, but after a quick search online, I couldn’t find anything specific to firmware files with this particular magic.

In the forum I originally stumbled on, there was a post referencing a header with size 0x11C. Looking at the next 4-bytes after the SBFH magic, you’ll see 1C 01 00 00. This is the value of 0x11C written in little-endian. At this point, we can be pretty confident we are dealing with a firmware header.

|

|---|

| The first 16 bytes of the file show the magic and the header size |

Since we are pretty confident the file header is indeed 0x11C bytes long, we may be able to visually see some patterns that stand out and can give us more clues as to what’s inside of the binary file we’re looking at.

|

|---|

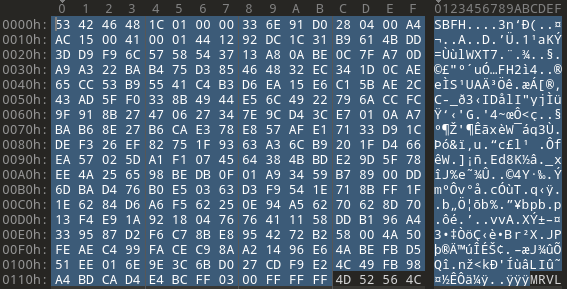

| First 0x11C bytes of the firmware file |

Conveniently, we see another 4 bytes of ASCII text, but this time, a quick web search returns some promising results. We also saw mention of Marvell firmware in the original Reddit post that started all of this. But we shouldn’t get ahead of ourselves just yet. Let’s see if we can make sense of any other fields in the first 0x11C bytes of the firmware header.

Overall, the header bytes look pretty random, like its entropy is high. This could mean the data is compressed, a hash, or a digital signature. It’s hard to say without the code in the firmware to perform updates (which may be right here in front of us!).

If we look at the first few dwords of the header, though, we see some periodic 0x00’s, which could mean there is more than just random gibberish. Since we’re dealing with firmware, we know the code has to get loaded into memory, so maybe one of the values is a memory address. Or, if this is a container header for the firmware, perhaps the program parsing this code needs to know the total file size to decompress or generate a hash. We can easily check the file size by selecting the entire file’s bytes (Ctrl+a). We see there are a total of 0x0015ADC0 bytes. We know, or at least safely assume, the file header is 0x11C bytes long, so if we look for something like 0x0015AD or 0x0015AC, we might see something we’re looking for. (Note: Remember, the file bytes are little-endian, but we write numbers in big-endian, so we’re looking for something like AC 15 00)

Sure enough, at 0x0F, we see 0x0015ACA4, which is the total_filesize (0x15ADC0) - file_header_size (0x11C). Now, we can create a 010 Editor template to help us keep track of the fields we’ve discovered.

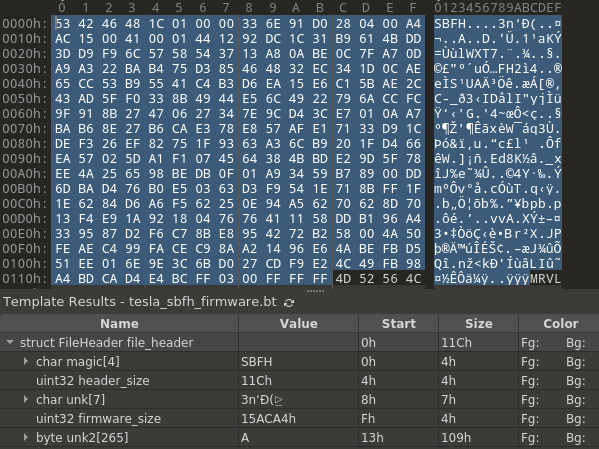

010 Editor Templates

010 Editor’s templates use c-struct-like syntax to provide a mechanism for processing and arranging the layout of a file. If we apply what we now know, we can create a template for the file header.

// File Header

typedef struct {

char magic[4]; // "SBFH"

uint32 header_size; // 0x11C bytes in this particular case

byte unk[7];

uint32 firmware_size; // Total size of the firmware blob

byte unk2[header_size - 4 - sizeof(uint32) - 7 - sizeof(uint32)]; // This is the rest of the header

} FileHeader;

|

|---|

| This image shows an example of how a template look when ran on a file in 010 Editor. |

Feel free to check out the template on my GitHub.

I tried poking around more on the unknown bytes but couldn’t find anything meaningful. I tried hashing the firmware blob (the data that comes after the file header) but didn’t see any hashes that matched. Granted, I didn’t try every possible hash, only the defaults that come with the version of 010 Editor I’m using.

Being confident of being on the right track to unwrapping this firmware, we can move on to the next blob.

Marvell 88MW30x Firmware

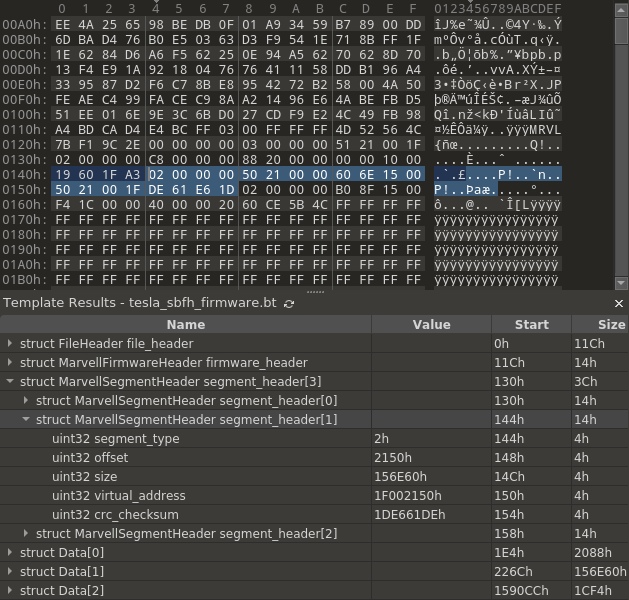

Searching online for firmware with the MRVL magic led me to this repo that shows the file format for Marvell 88MW30x firmware files. Upon immediate inspection, we can see that the firmware and segment headers match the wall connector’s firmware. Again, 010 Editor templates are handy here.

|

|---|

| By building out more of the template, we can highlight more firmware sections |

One thing to note is the virtual_address field in each segment’s headers. This virtual address is how the firmware loader knows the memory address to place the code in memory. This will be useful when loading this firmware into a disassembler like Ghidra.

Conclusion

There is still more we can learn about the SBFH file header, but for, now we know enough to be dangerous and move on to the next step of reverse engineering. It’s often more fun to immediately try throwing a binary firmware image into Ghidra and seeing what code will come out. Hopefully, if you’ve read this far, you’ll appreciate starting small and trying to understand all the underlying structure of the firmware before diving in.